Neoliberalism, the dominant ideology of modern capitalism, is under sustained challenge. For the past quarter of a century neoliberalism, sometimes called market fundamentalism, the policy of non-intervention in the economy, has been the ideology, and the set of policies that go with it, which has adamantly opposed the rights and attempted to drive down the living standards of the working class all over the world. Now the economic crisis is forcing the authorities to intervene, regulate, and even nationalise firms. Is neoliberalism dead?

It seems the neoliberal rulebook has been torn up. Martin Wolf,

economic guru of the Financial Times, dates the change from the

collapse of Bear Stearns last March. "Remember Friday March 14th: it

was the day the dream of global free-market capitalism died. For three

decades we have moved towards market-driven financial systems. By its

decision to rescue Bear Stearns the Federal Reserve, the institution

responsible for monetary policy in the US, chief protagonist of free

market capitalism, declared this era over. It showed in deeds its

agreement with the remark by Joseph Ackerman, chief executive of

Deutsche Bank that, 'I no longer believe in the market's self-healing

power.' Deregulation has reached its limits."

As the crisis bit into the popular consciousness, the popular press

recorded the same thought, on a lower intellectual level. The hard

right Daily Express headline screamed, "Don't let the spivs destroy

Britain (17.09.08)." The article began, "Millions of British families

are facing the destruction of their livelihoods as the nation's economy

teeters on the brink of catastrophe, brought low by the greed and

stupidity of spivs in high finance." Suddenly the Masters of the

Universe, the wealth creators in the City and Canary Wharf, had become

"spivs and speculators," to use Alec Salmond's phrase.

The Archbishop's of Canterbury and York have chipped in their three

penn'orth. Rowan Williams denounced the speculation, which had, "Been

the motor of astronomical financial gain for many in recent years". He

went on that the crisis shows, "The truth that almost unimaginable

wealth has been generated by equally unimaginable levels of fiction,

paper transactions with no concrete outcome beyond profit for traders".

John Sentamu told the bankers straight, "To a bystander like me,

those who made £190m deliberately underselling the shares of HBOS, in

spite of a very strong capital base, and drove it into the arms of

Lloyds TSB, are clearly bank robbers and asset strippers."

He makes an unassailable point, "One of the ironies about this

financial crisis is that it makes action on poverty look utterly

achievable. It would cost $5bn (£2.7bn) to save six million children's

lives. World leaders could find 140 times that amount for the banking

system in a week. How can they tell us that action for the poorest is

too expensive?"

These people are worried sick about the financial crisis. What, in

form, is a financial crisis is, in fact, a crisis of capitalism. In an

unplanned economy, money is the sole nexus between people. As Marx

explains, "As long as the social character of labour appears as the

monetary existence of the commodity and hence as a thing outside actual

production, monetary crises, independent of real crises or as an

intensification of them, are unavoidable." (Capital Vol. 3 p. 649)

Emergence of neoliberalism

Neoliberal ideology emerged as a result of the economic thunderstorm

that brought the great postwar boom to an end. In 1973-74 we saw the

first generalised crisis of world capitalism. The preceding period from

1948 to 1973 had proved to be a golden age for world capitalism.

Production went up year after year, as did living standards. In this

situation of full employment the capitalist could afford to make

concessions to keep the wheels turning and the profits rolling in.

After all, the working class, at least in the advanced capitalist

countries, had a very favourable bargaining position.

The ideology associated with the golden age was Keynesian economics.

Now it is not true that Keynesian remedies caused or prolonged the

great boom. This was explained at the time by Ted Grant (see Will there

be a Slump? 1960). However the era was such a contrast with the

interwar period of mass unemployment and struggle that the perception

of all classes of the population was that capitalism had changed

fundamentally. Booms and slumps, it was generally believed, had been

banished to the history books.

Clearly the 1973-74 recession came as an enormous political shock.

The working class internationally mobilised to defend the gains of the

postwar period. The ruling class, for their part, was determined to

drive down living standards and restore the rate of profit. As a result

of this clash, a revolutionary wave swept across the capitalist world.

All the earlier certainties were thrown up in the air and called into

question. In addition to rapidly rising unemployment the world economy

experienced spiraling prices. The immediate trigger for inflation was

the oil price crises of 1973 and 1979. Never before had we experienced

inflation together with recession. This was called stagflation. This

was the crucible that produced neoliberalism.

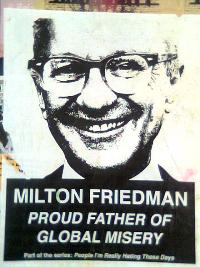

A

A

handful of right-wing economists, of whom Milton Friedman was the most

well known, had never swallowed the Keynesian myth that capitalism has

been tamed. They received more and more ruling class backing as

Keynesian economics went into crisis. By the end of the 1970s they

dominated economics faculties in the universities. Their ideas were

widely received, including by Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan,

who told Labour Party Conference in 1976, "We used to think that you

could spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by

cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all

candour that that option no longer exists, and in so far as it ever did

exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a

bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level

of unemployment as the next step."

This represented a rejection of any attempt at reflationary policies

in the face of growing unemployment. It was an acceptance of monetarist

economics and of capitalist ascendancy. Monetarism, which is part of

the canon of neoliberalism, is not just a dry economic theory. It is a

calculated assault weapon on the working class. The monetarists harked

back to the time before Keynes when economists admonished governments

not to interfere in the economy, but just keep a tight grip on the

money supply. If, as they sneered, the Keynesians were 'yesterday's

men', then they were 'the day before yesterday's men.'

Neoliberalism triumphant

Why should the government not interfere in the economy? Because the

doctrinaires believed the market (capitalism), left to itself, would

produce 'optimal' results. Markets get it right! This smug revival of

nineteenth century laisser faire ideology was a weapon against the

nationalised industries fought for by the working class, against the

mixed economy that gave workers some protection against the rigours of

the market, against the welfare state and all the gains made by the

workers in nearly a century of struggle against unfettered capitalism.

According to neoliberal principles even an attempt at redistribution

should be abandoned as an attack on the 'natural' outcome of market

forces since the existing division of income and wealth is produced by

the market. In effect the market was god. If there is unemployment,

then wages must be too high. Cut them to restore full employment. This

is madness, but madness that serves the ruling class well.

Associated with neoliberalism was talk of 'globalisation.' Tariff

barriers were coming down all over the globe. Capital was expanding

everywhere. Its proponents argued that 'globalisation' meant that

resistance was futile. Because capital was endlessly mobile, nation

states were becoming powerless. They had to reduce taxes on profits and

obey the multinationals' every wish or they would simply move their

money elsewhere. Regulation had to be torn up. Workers would be

blackmailed into accepting lower and lower wages or they would lose

their jobs altogether. It was a race to the bottom. Resistance was

futile! We have argued elsewhere that this was ruling class propaganda, a simplistic picture of reality.

Neoliberal triumphalism got an echo because of the collapse of the

Soviet Union and the associated Stalinist regimes in Eastern Europe.

Capitalism had won the Cold War! So it seemed there was no alternative

to capitalism (or 'the market,' as apologists came to call it). This

was the theme of Francis Fukuyama's 1989 essay The end of History?

Neoliberalism was at first believed to be so obviously opposed to

the working class interests that it could not be applied in a political

democracy. The workers would vote against it. So they imposed it as an

'experiment' in Pinochet's Chile, under conditions of military

dictatorship. After the 1973 coup, the military felt itself strong

itself to destroy free trade unions, sweep away the welfare safety net,

privatise many industries, open up all the county's resources to

imperialist exploitation and massively impoverish the working class.

Just what big capital wanted! Neoliberal policies were pushed through

by means of torture and assassination.

The Chilean nightmare

Pinochet

Pinochet

was persuaded by the 'Chicago boys', economic disciples of Friedman who

infested the corridors of power after the coup to conduct a sweeping

deregulation of the banks. This proved to be a disaster, leading to a

devastating monetary crisis in 1982. Pinochet was then forced to

re-regulate the banks in order to prevent a banking collapse.

The fact that neoliberal policies don't work and can be shown to

have never worked has never actually been a problem for their

advocates. The only sense in which neoliberal policies ever 'work' is

that they swing the balance of forces against the working class. That

is what they are intended to do.

Next up as a proponent of neoliberalism was Margaret Thatcher. The

British electoral system allowed Thatcher to have landslide victories

in the elections with at most 43% of the electorate. Her government

complacently presided over mass unemployment of over three million.

Some of their economic policies, such as sky-high interest rates that

choked off investment and caused sterling and British goods to become

completely uncompetitive on world markets, seem deliberately intended

to shed jobs and annihilate great swathes of manufacturing industry.

The unemployed were used as a whip against employed workers in order to

turn the tables against organised labour. Coal was stockpiled in huge

quantities as part of an intended showdown with the miners, seen as the

brigade of guards of the labour movement. A viable coal industry was

destroyed out of political spite. None of this was 'efficient' in the

normal sense of the word. It amounted to an immense squandering of

resources that could have been used to benefit society. But then,

capitalism does not have as its purpose social benefit. Private profit

is its driving force. Thatcher's mantra was 'there is no alternative.'

Millions of workers hankered back for the secure full employment and

rising living standards of the golden age. In one sense Thatcher was

right. That era had gone for good. Neoliberalism intended to restore

normal capitalist business as usual – and thoroughly nasty it was. The

only way to defend living standards now was to change society.

In the USA Ronald Reagan also pursued the neoliberal agenda, which

by the 1980s had become the dominant ideology of the capitalist world.

The international economic institutions – the IMF, World Bank and now

the World Trade Organisation – became fortresses of neoliberalism,

pitilessly bullying the poor countries on behalf of imperialism to open

up their services, industry and agriculture to the rich countries,

privatise their industries and make their natural resources freely

available to foreign looters. The councils of the European Union,

especially the European Central Bank when it was founded, became

increasingly influenced by market fundamentalism.

Reagan declared that "government was not the solution, but the

problem". As head of the government he strove to make that true for the

working class. One of his first acts as President was to destroy the

air traffic controllers' union. When PATCO went on strike in August

1981 Reagan declared the strike illegal and sacked more than 11,000

strikers. Neoliberalism is a return to the economic liberalism of the

nineteenth century. Socially it is not liberal, but necessarily

authoritarian and repressive of the working class, as its central aim

is to restore the unfettered hegemony of capital.

Even more important than the election of Reagan was the appointment

of Paul Volcker as head of the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, in

1979. Volcker proceeded to 'deal with' inflation by yanking up interest

rates and allowing mass unemployment to develop. Since the USA was the

hegemonic capitalist power, this caused interest rates to rise

all over the world. Financial shenanigans from the previous decade came

back to haunt the world economy. In the two oil price crises of 1973

and 1979 the oil exporting countries had won a fistful of

'petrodollars' on the back of the oil price rises. They actually didn't

know what to do with all this money. The big western banks had been

congratulating themselves at how they had recycled the petrodollars.

They took this money and hurled it at less developed countries in the

form of third world debt, twisting the arms of finance ministers in

Latin America to take the cash. But the increase in interest rates in

the 1980s made these less developed countries unable to keep up the

payments.

Mexico was first to default in 1982. Throughout the decade the IMF

moved pitilessly through Latin America demanding their pound of flesh

on behalf of the imperialist powers. They demanded that the governments

of Latin America stop trying to improve the living standards of their

citizens and instead pump out natural resources to pay their debts.

This was called export led industrialisation, all part of the

neoliberal project.

The result was a catastrophe for Latin America, the 'lost decade.'

From 1980-89 output and living standards fell throughout the continent.

Latin America's share of world output fell from 6% to 3% over the

decade. Whereas output had gone up by 2.5% a year through the crisis

decade of 1973-80, from 1980-89 it fell by 0.4% a year. Imperialism got

its pound of flesh all right. As late as 2005 Latin America still had a

debt burden of $2.94trn, most of it inherited from the 1980s. This was

nearly two thirds of all 'emerging market' debt.

The scars still show. In 2003 a CEPR Briefing Paper (Another Lost

Decade? by Mark Weisbrot and David Rosnick) predicted miserable growth

of 0.2% from 2000-2004 - 1% for the whole period. They pointed out that

over the previous 20 years 1980-99 the region grew by just 11%, a worse

result than during the Great Depression. By contrast in 1960-79 Latin

America grew by 80%. These figures paint a picture of the poverty,

malnutrition and disease that are the achievements of neoliberalism.

Socialists and defenders of the common people are entitled to stuff

these ugly realities down the throats of the proponents of

neoliberalism and globalisation. The economic crisis is inevitably

producing a crisis in the ruling ideas – which, as Marx explained, are

the ideas of the ruling class.

All change

Now it's all change. Laisser faire is all very well when the profits

are rolling in and when it is only the poor and the working class who

call for state intervention to protect them from the cruelties of

market forces. It's a different matter when the hides of the capitalist

class are at risk. Then they behave like hapless victims who need all

the state assistance they can get. And, as far as they are concerned,

if ordinary working class people have to dip their hands into their

pockets that's the way it's got to be.

Ruth Sutherland agreed with the great and the good quoted earlier

(Observer 28.09.08), "In the US, hundreds of billions of dollars of

banking risk will be transferred to the federal government, adding to

America's huge burden of debt and increasing its reliance on foreign

investors…Policymakers face formidable challenges: fighting the fire,

then repairing the financial system while keeping a lid on inflation,

then putting in place effective new regulation. The worst is still to

come. The high drama over Hank Paulson's rescue plan has been so

riveting it has relegated everything else to a sideshow - even the

collapse of Washington Mutual, the biggest bank failure the US has ever

seen. But deeper questions lie beyond the wrangling over the bail-out,

as the Archbishops of Canterbury and York highlighted in their

interventions in the debate about the future of capitalism. If there is

a positive side to this terrible crisis, it is that it has given us a

once-in-a-generation opportunity to slay the myth of the omnipotent

market.

"People in the City have never particularly claimed moral

justification for their activities, but they were able to assume a

mantle of authority because of the sheer volume of money they made - or

appeared to make. Almost everybody - politicians, regulators,

journalists, voters, mortgage borrowers - accepted the City at its own

valuation; whether we approved or not, cowboy capitalism was considered

unassailable.

"Those who argued that enormous bonuses were bad for the fabric of

society, because they heightened inequality and undermined people's

perception of fairness, were looked upon as unspeakable lefties, or

just jealous. Those who argued for stronger regulation were dismissed

as meddlers, bureaucrats and stiflers of innovation. And those who were

uneasy about certain activities were lectured on how the trickle-down

of wealth would benefit everyone."

She concludes, "This crisis should prompt us to reappraise our

relationship with money and debt, and to think hard about how we can

create a fairer and more inclusive version of capitalism. There should

be no return to the market's false gods."

On a less idealistic, but still urgent, note Christopher Cox, chair

of the US Securities and Exchange Commission declared, "The last six

months have made it abundantly clear that voluntary regulation does not

work."

Even more forcefully, David Rothkopf, a senior Commerce department

official during the administration of President Bill Clinton, says the

world is at a turning point. "This is a watershed," he says. "This is

the end of 25 years of Reagan-Thatcherism, 'leave it to the market,

less government is better government'. That is over - period."

And Ben Bernanke, head of the Fed, sums up the new mood, "There are

no atheists in foxholes and no ideologues in financial crises."

President Sarkozy agrees with this sea change in consciousness.

"(The) idea of an all powerful market without any rules and any

political intervention is mad." So the unchallenged economic orthodoxy

of yesterday is now mad! He goes on, "Self regulation is finished.

Laisser faire is finished. The all-powerful market which is always

right is finished."

This is all trenchant criticism – unprecedented for a generation.

None of these critics, of course, suggest an alternative to the

capitalist system. They all sound as if they feel that they have been

bamboozled by the hocus-pocus of neoliberalism. Their outrage is

directed at financial 'geniuses' they now realise were simple

charlatans, who have been helping themselves to the good things in life

at our expense and landing us all in the mire in the process.

The New Deal

Their call is for regulation. Capitalism, we are told, would be a good

system if only it were adequately regulated. What is the real relation

between capitalism and regulation?